Phineas Gage (1823-1860) is one of the earliest recorded cases of severe brain injury in medical history. What makes Gage’s case especially interesting isn’t just his survival after the brain trauma, but also the profound personality change he underwent. This radical shift in personality raises intriguing questions about the mind-body, brain-mind, and emotion-reason connections.

Phineas Gage (1823-1860) is one of the earliest recorded cases of severe brain injury in medical history. What makes Gage’s case especially interesting isn’t just his survival after the brain trauma, but also the profound personality change he underwent. This radical shift in personality raises intriguing questions about the mind-body, brain-mind, and emotion-reason connections.

Phineas Gage was the foreman of railroad workers in Vermont, responsible for blasting through rocks to build railway tracks. This process wasn’t done with modern techniques back then. Today, explosives are placed, and the explosion is triggered remotely. But in the 1800s, things were different: critical holes were drilled deep into the rock, filled with gunpowder, and a fuse was placed in each. Some sand would then be added on top, and before lighting the fuse, the gunpowder was tamped down with an iron rod to ensure the blast would impact the rocks effectively. This rod-tamping process was tricky and delicate, but Gage, using a custom-made rod, had become a virtuoso at it. When all was set, everyone would retreat to a safe spot, and someone would light the fuse before quickly running away.

Gage was known as the fastest, most efficient, and skilled foreman at the company. Thanks to the discipline and work ethic he brought to his work, projects were completed on time. With his social graces, he had also become a favorite among his team. He was described as a “shrewd, smart businessman” and kept himself away from the questionable attractions of local taverns. He was popular with both his family and friends.

On September 13, 1845, 25-year-old Gage and his team were working near Cavendish, Vermont, on the Rutland and Burlington railroads. It was a hot afternoon, around 4:30. Gage loaded a hole with gunpowder and the fuse, instructing his assistant to cover it with sand. Someone called out from behind him, and as he glanced over his right shoulder, distracted, Gage began tamping the powder with the iron rod before the sand had been added. The powder instantly ignited, exploding directly toward Gage.

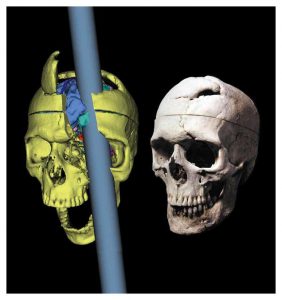

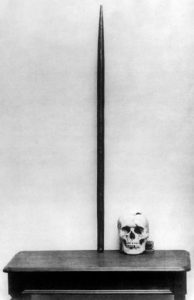

The blast was so powerful that the whole crew froze, taking a few seconds to grasp what had happened. The explosion was strange because the rock hadn’t moved. What was even stranger was a whistling sound, as if a rocket had been launched skyward. It quickly transpired that the iron rod had entered Gage’s left cheek, pierced through his skull from the base, passed through the front of his brain, and exited through the top at high speed. This rod, over a meter long, weighing more than 6 kg, with a diameter of 3.5 cm on one end and 6.35 mm on the other, was found more than 30 meters away, covered in blood and brain matter. Gage had been thrown to the ground. Dazed, but miraculously conscious, he lay stunned in the afternoon sunlight.

In the minutes following the accident, Gage got up and started to walk. As his colleagues recovered from the shock that he wasn’t dead, they placed him in a cart and transported him to his boarding house a kilometer away. When they arrived, Gage dismounted the cart with minimal help from his friends. He was attended to by local physician Dr. John M. Harlow, who cleaned the wounds, removed small bone fragments, and repositioned larger bone pieces. He then placed a wet dressing over the large wound on his head and covered it with adhesive bandages. No surgical intervention was performed; rather, the wounds were left open to drain.

A few days after the accident, Gage’s unprotected brain developed an infection, and he fell into a semi-comatose state. His family prepared for his death and began making arrangements, but Gage survived the illness. Dr. Harlow drained 235 milliliters of pus from an abscess in Gage’s skull, which could have leaked into his brain with deadly consequences. With the resilience of youth, Gage quickly recovered. By January 1, 1849, he was already seemingly leading a normal life.

Dr. Harlow noted that Gage’s reasoning abilities remained intact, but his wife and close friends observed significant and dramatic changes in his personality. Interestingly, no mental effects of Gage’s brain injury were formally documented until 1868. A report published in the Bulletin of the Massachusetts Medical Society described the changes as follows:

“His contractors, who regarded him as the most efficient and capable foreman in their employ prior to his injury, considered the change in his mind so marked that they could not give him his place again. He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operation, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn for others appearing more feasible. In this regard, his mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was ‘no longer Gage.’”

This detailed account highlights the profound and lasting impact of Gage’s brain injury on his behavior and character.

The damage to Gage’s frontal cortex resulted in a complete loss of social inhibition, leading to inappropriate behavior. While he retained core cognitive abilities such as attention, perception, memory, intelligence, and speech, he lost his learned social norms and ethical dispositions. Skills uniquely human—such as predicting outcomes in complex social settings and planning accordingly—were obliterated due to the injury to a specific region of his brain. Gage could no longer make sound or balanced decisions, instead acting impulsively and recklessly without hesitation. Either his value system fundamentally changed, or his existing values no longer influenced his actions. In essence, the tamping iron had performed a rudimentary frontal lobotomy on Gage.

However, the precise areas of his brain that were affected remain a topic of scientific debate. The extent of the damage can only be inferred from the rod’s trajectory, estimated based on the skull fractures. Current analyses suggest that the iron rod primarily damaged Gage’s left prefrontal cortex rather than the right, which houses key language areas. Gage’s case became the first documented evidence of the frontal cortex’s critical role in shaping personality and behavior.

Today, it is well established that the frontal cortex plays a significant role in social perception, decision-making, and executive functions. Yet, despite advances in neuroscience, the relationship between the brain and the mind remains enigmatic, and modern neuroscientists only marginally surpass 19th-century understanding in fully unraveling this complex connection.

What happened to Phineas Gage after the accident? Unable to return to his previous job, Gage reportedly traveled across New England and even Europe, earning money by showcasing himself and his infamous iron rod. It is said that he briefly exhibited himself as a curiosity in Barnum’s circus in New York. However, like the details of his neurological damage, the accounts of Gage’s life post-accident are a subject of debate.

What is certain is that he worked as a bus driver from 1851 until his health began to decline. He started at the Dartmouth Inn in Hanover, then spent about 18 months driving buses in New Hampshire before moving to Chile, where he worked for approximately seven years. By 1859, with his health deteriorating, Gage returned to live with his mother. On May 20, 1860, 13 years after the accident, he died in San Francisco from complications related to epileptic seizures. Unfortunately, no autopsy was performed at the time.

In 1867, Gage’s body was exhumed from San Francisco’s Lone Mountain Cemetery, and his skull, along with the tamping iron, was brought to Dr. Harlow by Gage’s brother. Today, both Gage’s skull and the rod that caused his injury are preserved and displayed at the Warren Anatomical Museum in Harvard Medical School.

By Nazım Keven

Sources and further reading

Costandi, M. 2006. The incredible case of Phineas Gage, at https://neurophilosophy.wordpress.com/2006/12/04/the-incredible-case-of-phineas-gage/

Damasio, H., Grabowski, T., Frank, R., Galaburda, A. M., & Damasio, A. R. 1994. The return of Phineas Gage: Clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient. Science. 264, 1102–1105.

Ratiu P. & Talos I. F. 2004. The tale of Phineas Gage, digitally remastered. New England Journal of Medicine. 351: e21-e21.

Van Horn, J. D., Irimia, A., Torgerson, C. M., Chambers, M. C., Kikinis, R., & Toga, A. W. 2012. Mapping connectivity damage in the case of Phineas Gage. PLOS ONE, 7, e37454.